Some will have us believe that we are living in interesting times … or troubling times … or add-your-own-anxiety-label times. To me, these are unsettling times.

There is something unsettling about the present moral climate, and it has little to do with any single cause, country, or conflict. It has more to do with how morality itself seems to operate—how it circulates, how it authorizes and sanctions speech, how it decides when outrage is urgent and when silence is acceptable or unacceptable. There is a rush to define, categorize and label us by our choice on the menu of morality.

So, the question I keep returning to is a simple one: what else is morality doing now?

We tend to treat morality as a stable compass—an internal sense of right and wrong that guides action. Yet in practice, morality increasingly behaves like a system of signals. It organizes identity. It marks belonging. It tells us not only what to care about, but how to care, when to speak, and—perhaps most importantly—when not to.

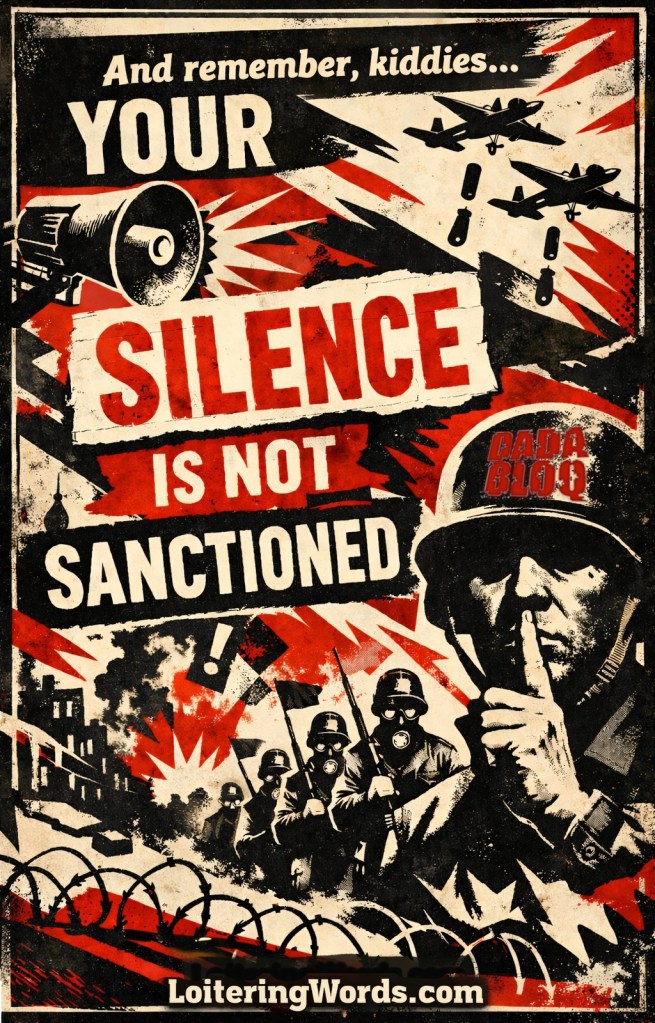

This becomes visible in moments of asymmetry. Large-scale protests erupt for one injustice, while another—equally brutal, equally human—passes with comparatively little public noise or fanfare. The silence feels eerie, not because silence is always wrong, but because it appears selective, patterned, and disciplined—and it is certainly labeled that way by some. Silence itself begins to function as a message.

At that point, morality is no longer only about suffering or dignity. It is also about permission.

We like to believe moral speech flows from conscience. Increasingly, it flows from institutions, movements, and sanctioned narratives. Speech becomes acceptable not when it is thoughtful or humane, but when it is legible—when it fits an existing moral grammar. When it does not, it risks being ignored, sidelined, or quietly disqualified.

This is where moral confusion sets in. Not confusion in the sense of ignorance, but confusion born of over-coordination. Too many cues. Too many rules. Too much fear of saying the “wrong” correct thing. Morality becomes something we perform for an audience rather than practice with one another.

When that happens, conscience starts to look like a non sequitur. “And what of humanity?” you ask. The sanctioned answer seems to be, “What of it?”

History gives us sobering examples of where this leads. Groupthink is the everyday mechanism; catastrophic moral collapse is the endpoint. Nazi Germany did not arise from a population devoid of moral language, but from one saturated with it—obedience moralized, dissent pathologized, conscience reframed as betrayal. The lesson is not about comparison; it is about structure. When morality is externalized, internal judgment withers and dies in gaslight and gas chambers.

This does not mean people today are uniquely cruel or insincere. On the contrary, many are deeply motivated by a desire to reduce harm. The problem is not caring or lacking of empathy. The problem is how care is routed—through institutional approval, reputational safety, and collective choreography.

It should irk us that certain injustices become sites of disproportionate moral amplification, while others remain symbolically inconvenient. This does not require malice. It requires a system—a social machine—in which moral urgency is filtered through ideological fit, coalition maintenance, and media traction. Protest becomes symbolic rather than instrumental; alignment matters more than outcome.

At the same time, silence can itself become a tool. It can shame. It can discipline. Of course, it can also imply that the absence of speech signals ignorance or indifference, even when that very silence is born of caution, complexity, or moral hesitation. And, as such, it is true that over time, people learn not only what to say, but what not to notice too closely. They are conditioned to move along, to not look at the man behind the curtain … and to walk, not run, to the slaughterhouse.

This is where humanism begins to matter—not as sentimentality, but as resistance.

Humanism insists on the irreducibility of persons. It resists abstraction. It refuses to collapse human suffering into symbols, slogans, or strategic assets. It recognizes how easily systems—political, moral, or cultural—turn people into instruments.

There is an unexpected lineage here. The Dadaists, often dismissed as nihilists, were reacting to a world in which reason, culture, and moral certainty had marched obediently into mass slaughter. Their absurdity was not a rejection of humanity, but a refusal of false coherence. When meaning itself had been conscripted, refusal became a form of care.

That refusal feels relevant again.

The zeitgeist of our times reveals that moral language is abundant, yet moral discernment feels constrained. Institutions prefer alignment to reflection. Movements reward repetition over hesitation. Liberal systems, in particular, struggle with unsanctioned moral speech—even when that speech emerges from within their own professed values … like this essay, for example. Oh the things you may not read, but I’ll write it anyway.

This is not an argument against protest, nor against politics. It is an argument against outsourcing conscience.

Let me make one thing perfectly clear: yes, we should be disturbed by the brutality and inhumanity unfolding in Iran—by a government turning its violence on its own people, by the silencing of dissent, by lives treated as disposable. Yes, awareness matters, and so does not looking away. However, recognizing injustice does not mean flattening everything into the same moral story. Iran is not Gaza, Gaza is not Ukraine, and Ukraine is not Iran. These situations grow out of different histories, different power dynamics, and different political realities. Moral seriousness is not proven by automatic alignment, and in that sense, people who are not directly involved should not be pushed into action through shame or accused of complicity because they are silent. To many, the heart may break—but dying for the cause is not required, and marching into a war that is not their own is not a moral obligation.

If morality is always something we demonstrate for institutions rather than negotiate with one another, we should not be surprised when it hardens into groupthink. My concern has always been that if outrage must be approved before it is expressed, silence will continue to feel eerie—not because people do not care, but because care has been bureaucratized … and freedom of speech quashed.

The question, then, is not which cause deserves more attention. The question is whether we still trust ourselves—and each other—to practice morality without scripts.

That trust is fragile. Yet without it, morality risks becoming just another system we comply with, rather than a responsibility we carry.

And when that happens, we may find ourselves speaking fluently about justice, while quietly forgetting how to listen to conscience at all.

All through the year, give the gift that keeps on confusing—one of my novels! My latest absurd work is Tricksters, Crackers and Gods, part of my Lost Florida series. Available in Kindle and Paperback. Read it. Gift it. Do it.