Authority is usually most anxious when it has to ask where authority comes from.

I was reading the Gospel of Matthew this week—somewhere around the stretch where authority is questioned and hypocrisy is named without much ceremony. There is a moment where Jesus is asked, rather pointedly, “By what authority are you doing these things?” It is a familiar question. Not theological, really. Institutional. Radical, perhaps, but not reckless.

The assumption behind it is simple enough: authority must come from somewhere recognizable. It must be granted, verified, stamped, and preferably issued by people who already have it—so they say, whoever they are. Otherwise, what you are doing may be interesting, even provocative, but it cannot be taken seriously—especially by those whose authority has been safely invested in themselves. The usual suspects, who most certainly have died and left themselves to be boss.

That question has aged remarkably well.

It shows up wherever systems exist to regulate legitimacy—religious, professional, cultural. It has a way of sounding reasonable even when it is doing something else entirely. Often, it is less about standards and more about comfort. Less about quality and more about order. A way of asking, Are you one of us?—or perhaps more bluntly, Show us your papers—without having to say it out loud.

What is striking in Matthew is not simply that Jesus challenges authority, but how he does it. This is not rebellion for its own sake. It is not contrarianism dressed up as virtue. It is something more unsettling: a refusal to borrow authority he does not need. His stance is not performative. It is internally justified. He knows what ground he stands on, even as others work to diminish him. That kind of confidence reads as insolence to those who rely on position rather than substance.

It is, in its own way, punk—though without the theatrics. Punk with receipts, you might say.

And then Matthew moves, quite deliberately, to hypocrisy.

Not hypocrisy as outright deceit, but hypocrisy as substitution. Appearance replacing substance. Role-playing standing in for responsibility. Authority performed rather than inhabited. The critique is not that rules exist or that structures matter. It is that they become costumes—ways of appearing legitimate while avoiding the far less comfortable work of self-examination and accountability.

That distinction feels uncomfortably current.

We live in a world unusually well supplied with credentials, endorsements, badges, affiliations—and with them, the quiet sanctioning or ostracizing of others. Entire ecosystems exist to assure us that growth has occurred because a process has been completed, a box ticked, a logo or a mark of verification displayed. Sometimes this is intentional, even chosen, and there is nothing inherently wrong with that. The problem begins when recognition is mistaken for development, and authorization is confused with authority itself.

This is where hypocrisy slips in unnoticed—not as malice, but as habit.

What Matthew exposes is not the absence of authority, but its hollowness when it is never internalized. Titles remain. Positions hold. Hypocrisy fills the vacuum. Yet something collapses under even mild questioning. What looks like confidence turns out to be scaffolding. What claims legitimacy cannot stand without constant reinforcement. And that’s when the eyes begin to dart—searching for confirmation, allies, or at least someone else willing to nod along.

Jesus’ indignation, by contrast, is not borrowed. It does not appeal upward. It does not ask permission. It rests on lived conviction and experience—on an authority that exists whether or not it is recognized. That is precisely why it unsettles, triggering much gnashing of teeth. Authority like that cannot be granted, and it cannot be revoked. It is not conferred by institutions, nor destroyed by their disapproval.

Which may be why the question “By what authority?” still provokes such anxiety in some quarters—not because authority should never be challenged, but because truly inhabited authority exposes those who only perform it.

And that answer—uncomfortable, uncredentialed, unsanctioned, and stubbornly internal—remains, rather inconveniently, unaccredited.

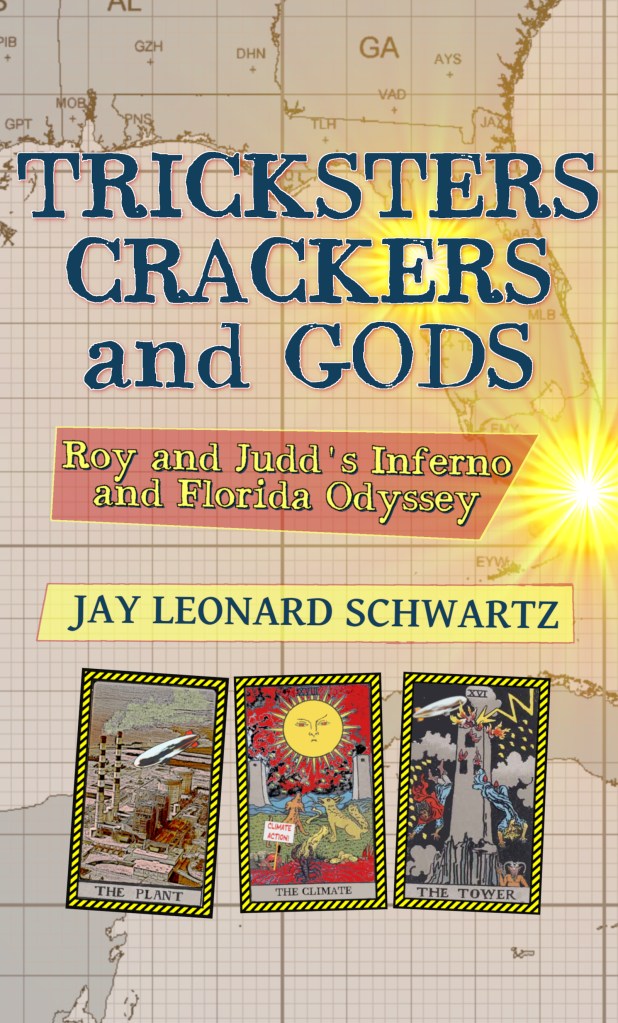

All through the year, give the gift that keeps on confusing—one of my novels! My latest absurd work is Tricksters, Crackers and Gods, part of my Lost Florida series. Available in Kindle and Paperback. Read it. Gift it. Do it.